The sign of

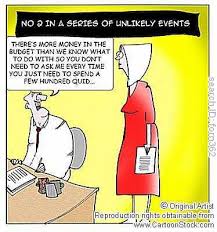

f is sometimes pursued and valued as though it were some kind of ancient idol. (The opening scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark comes to mind.) It's taken for granted that it's a necessary part of the processes we use to produce product. But what does the sign off really mean? When you get that signature on the document (or give yours), what is the sign off saying and what are the expectations of both parties going forward?

f is sometimes pursued and valued as though it were some kind of ancient idol. (The opening scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark comes to mind.) It's taken for granted that it's a necessary part of the processes we use to produce product. But what does the sign off really mean? When you get that signature on the document (or give yours), what is the sign off saying and what are the expectations of both parties going forward?Webster's online dictionary defines "sign off" as:

to approve or acknowledge something by or as if by a signature

Hey, that sounds pretty innocuous. I showed you something, or did something for you, and you're just signing a piece of paper that says you saw it, or I did it. But of course, the benign nature of that thought belies the social complexities and implications of what that signature really means.

On one level, it's an issue of trust. Why do you need my signature? Isn't it enough that I told you verbally that it's fine? If we worked in a world of implicit trust, that might be OK. But if you're the one looking for that signature from a manager or client, and heard that question, what are the chances you would respond "yes, sure, it's fine?" I say the chances are slim and none. If you could take it on verbal approval, then chances are:

1. The decision or deliverable in question is very minor,

2. Your organization is extremely small (and likely with a very flat organizational hierarchy), and/or

3. You really DO work in an organization with a model of implicit trust (this is rare if (2) is not true).

So if we don't trust each other enough to take everything on verbal approval, the question is why not? What are we afraid will happen if something goes wrong?

In THAT question lies the core issue. It's not what happens when everything goes well ... when the product is delivered on time, on budget, free of defects. At that point, everyone is happy, and someone throws a party. Maybe the only person unhappy with the lack of formal sign off in that situation is the person whose job it is to make sure all the boxes were checked for process' sake.

But when things DO go wrong -- major defects make it into production ("QA is the problem"), business owners or customers report that product features aren't what they wanted ("Requirements are the problem") or delivery is very late or well over budget ("OK, who did it?") -- THAT is when the true nature of the formal sign off shows. That's when fingers get pointed and people dive for cover ... behind the sign off.

I submit that at its core, the formal sign off serves mainly as an abdication of responsibility for a deliverable, or transference of that responsibility to the signatory.

This is why people are so apprehensive to sign off. Because at worst, by signing, the signatory puts him/her self on the hook for the deliverable on which they've just signed off. They've accepted responsibility for something they've likely had no hand in producing, but for which they have to answer. And when things go wrong, they'll be left holding the bag. This is an issue of the culture of the process.

Imagine a large river being fed by several small streams. At the point where each stream feeds into the main river, there's a lock. Water flows from each stream into the main river, but once it's contributed a certain amount, the lock closes. When a storm hits at the mouth of the river, and water is pushed back upstream, the locks are closed and the streams are protected, but the main river (and its surrounding banks) is devastated. This is a metaphor for the classic sign off when things go wrong, and the real tragedy is that in this model, nobody is responsible for the successful delivery of the product (except maybe the last signatory). Everyone else has plausible deniability. If you're contributing to the product, and something goes wrong because of your work, but someone else signed off on it, you can make a case that you're not responsible because they accepted both your work product and the responsibility when they signed off. It doesn't mean they won't try to pin it on you, but in the spirit of legal documents, you hold up the paper and say "I have your signature right here. You said it was correct and authorized it."

Now, contrast this with the model we use in Agile, specifically Scrum. We take a cross functional team, combine that with a business Product Owner and a Scrum Master, and emphasize that together they are the team, together they are collectively responsible for the successful delivery (or failure) of the product. We move away from the silo mentality that fosters people protecting their camp (or stream) at the expense of the product. We move to putting the product first, by ensuring that the product owner is prioritizing the product backlog to ensure we're working on the items with the highest business value first, in every iteration. And we emphasize continuous, open communication on the team.

Don't misunderstand me. I'm not saying that Agile or Scrum is some magic bullet to avoid the contentious atmosphere that the traditional sign off can foster. Is it possible to poison an Agile development effort by sticking to the old psychology of the sign off? Absolutely. What I am saying is that it provides a framework that can encourage the cultural change that is necessary to change that atmosphere. It's not in our nature and it's not easy ... it takes a willingness by the parties involved to give up the protection of the sign off, and sign up for shared success or failure. Implement this cultural shift in your team or organization, however, and trust and a shared sense of ownership of the product will cement the team together, stronger than the sum of its parts.

David Babicz is a Senior Consultant with Solstice Consulting, based out of Chicago. Dave has over 12 years of experience delivering IT solutions. He is a Certified Scrum Master, and expert in Agile methodologies.

Reference: blogs.computerworld.com